Classic Cars for Modern Music

Many of us who have ever fallen in love with a particular Blue Note album cover know there's a chance Reid Miles designed it. This week, we focus on why those beautiful cars kept appearing in his work.

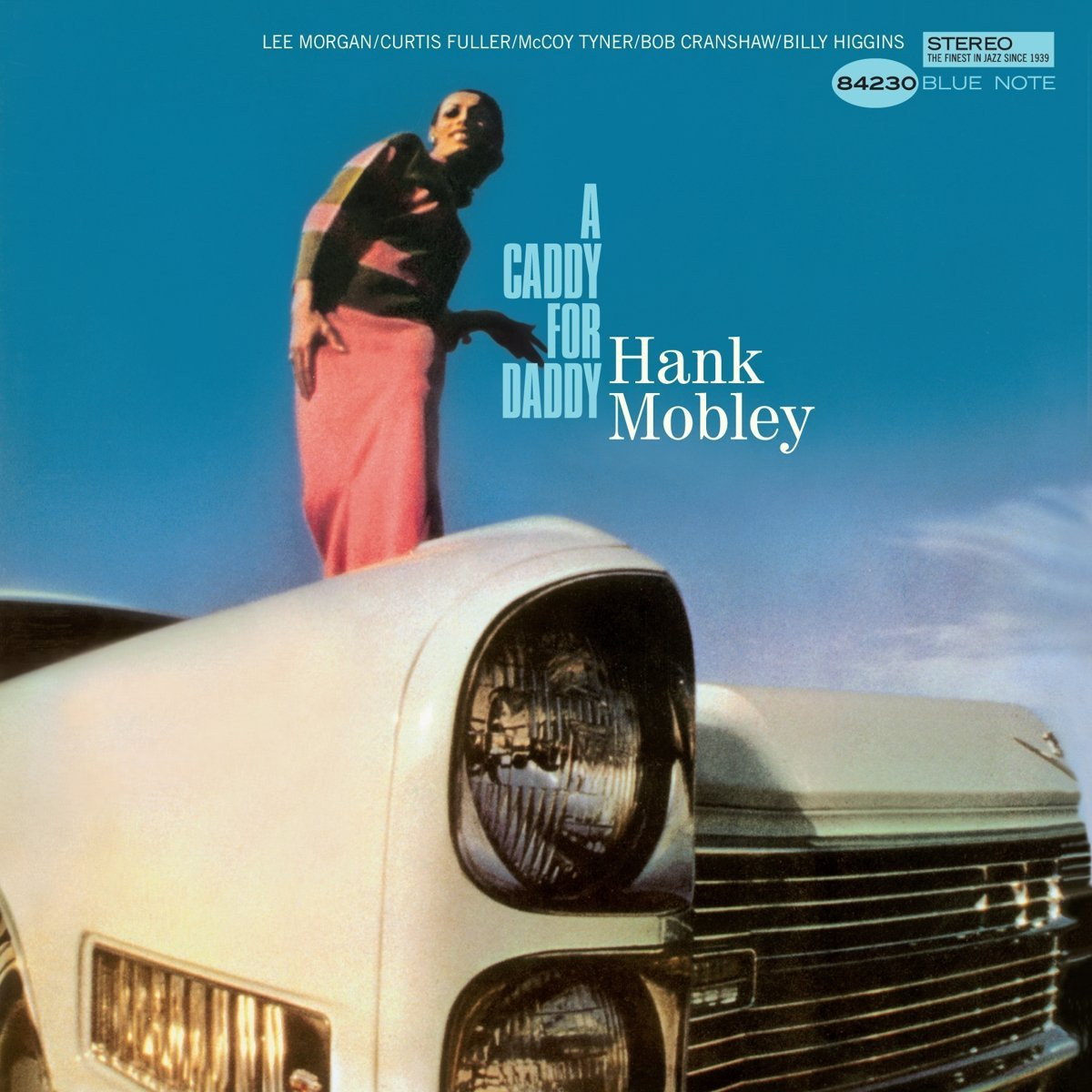

Reid Miles' photography and design for Hank Mobley's A Caddy for Daddy, 1967

Reid Miles

As the story goes, Miles ended up at Chouinard Art Institute following his service in WWII because he was pursuing a love interest (some notable names to emerge from Chouinard's student ranks include the animator Mary Blair, the designer Neil S. Fujita, and the painter Ed Rushca). While the relationship may have failed, Miles found himself studying at a fantastic institution that especially catered to designers and animators. The school was in part supported by Walt and Roy Disney, which only benefited them in the sense that they never had to look far to hire their next group of animators. Miles never finished his studies at Chouinard, but he took his acquired skills and headed to New York City to pursue a career in design.

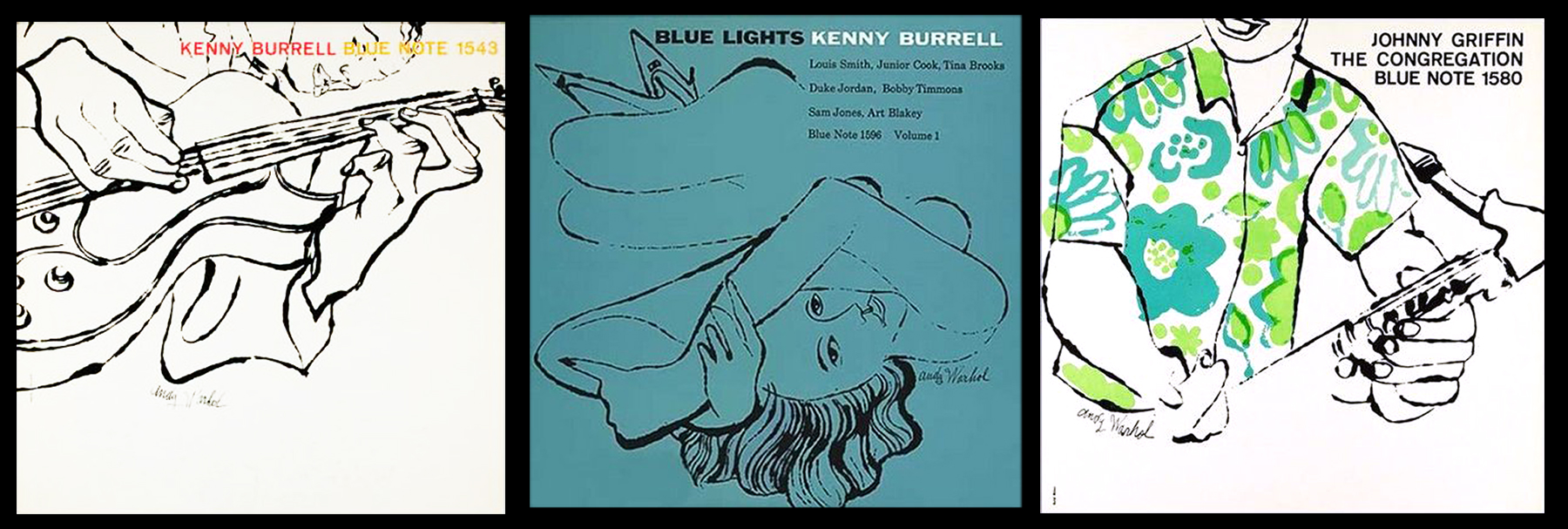

Miles would not make his "romantic mistake" again, seeming to gain more interest in work and less interest in human relationships as the years passed. For a 1978 interview in People Magazine, Miles said, "For me work is an upper, a great high. I have no personal life, I don't want it." By that point he was working in a vast, 10,000 square foot studio in Hollywood and producing images for clients including Coca-Cola and Kellogg's. But when he initially began working for Blue Note Records, it was the mid-1950s in New York City and the company had just started production for 12" (as opposed to 10") vinyls. Reid was most interested in playing around with the type in his images, and if there were specific images used for the cover, they often came from the camera of Francis Wolff or the brush of artists such as Andy Warhol and Phil Hays.

Three different collaborations between Andy Warhol and Reid Miles for Blue Note Records

The Turn to Photography

Reid Miles' talent was quickly recognized during his early years in 1950s New York City, earning him the position of art director at Esquire. His temperament made it difficult for him to exist in a collaborative office environment, often leading to his dismissal from several organizations through the years. It seems one might be able to call Miles' working style as obsessive. He often treated his designs as "total works of art," choosing the models, the costumes, the settings and the moods for any photography shoots that were needed to accompany his type treatments. At a certain point, Reid thought that it might be easier to to take his own photographs rather than try to instruct someone else how to take the photography he was looking for.

Thus in the 1960s, we begin to notice a shift in the credits on the back of albums which Miles' designed. Rather than see a listing for his design and a separate credit for the photographer, it is simply documented that Reid Miles was responsible for both. This did not mark a sour point in the relationship between Miles and Francis Wolff. In an interview with blogger Gerald Watson, photographer Wayne Adams (a former assistant for Miles) says that it seems that Wolff and Miles "got along famously" and was also close with Alfred Lion, the other owner of Blue Note. Perhaps this was the result of Lion's overall concern that he find someone who could help visually mirror the "modern" sounds of jazz music. He found that someone in Reid Miles and if Blue Note gained faith in Reid initially because of his typography skills, it seems to have only grown when he began making his own photographs.

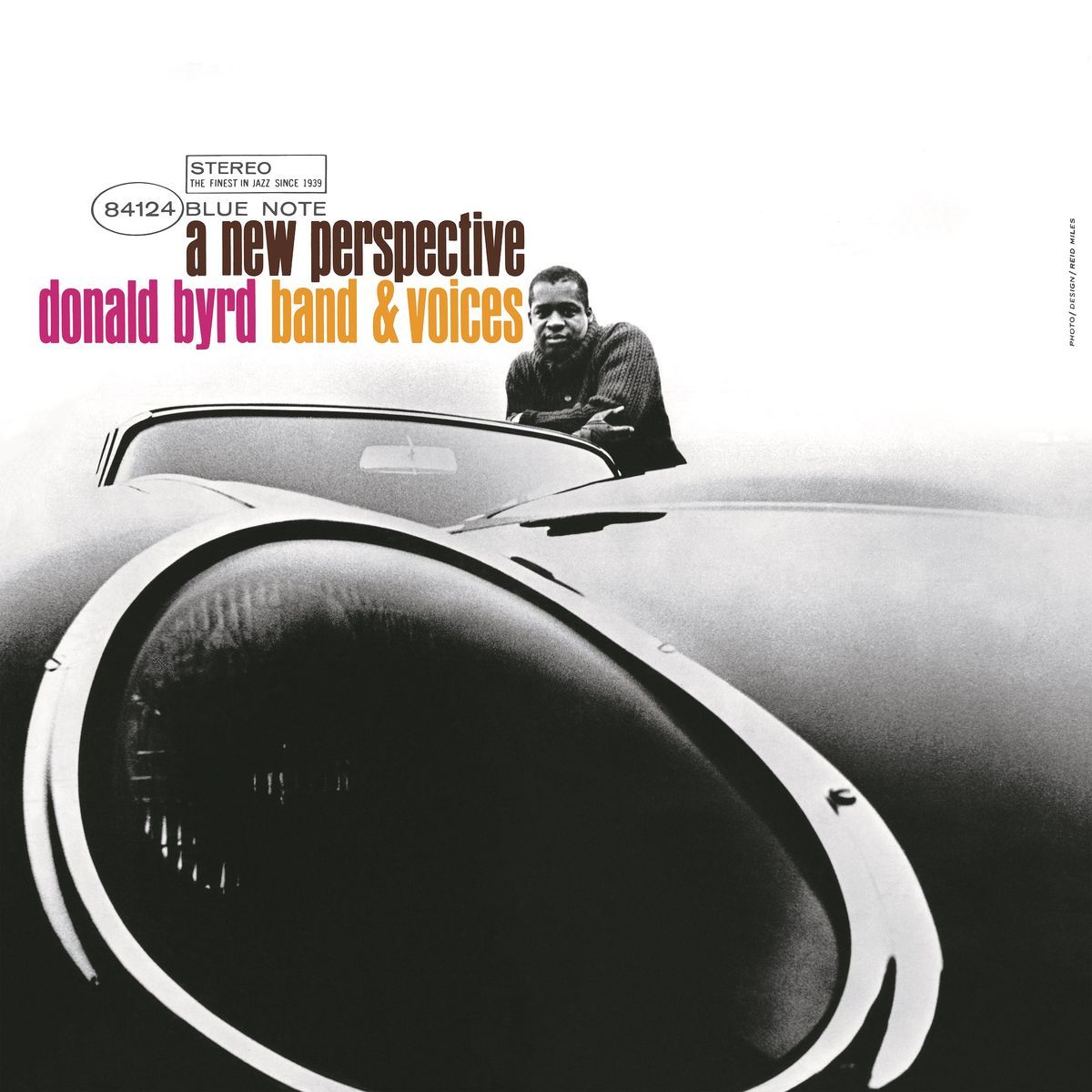

Photography and design by Reid Miles for Donald Byrd's A New Perspective, 1964

The Personal and the Professional

It is well documented that Reid Miles did not possess any particular love of jazz music. When it came to the aural arts, he preferred classical and it is thus tempting to understand his album cover work for Blue Note as somewhat detached or removed from his personal interests. But looking at a few particular albums, we can see that one of Miles passions does start to come through: beautiful automobiles. Fellow car enthusiast Max Fields has written that Reid was quite taken with what we would now call antique, classic and/or collector cars when they knew each other in the 1980s. At that point in his life Miles owned both a 1932 Lincoln and a 1949 MG TC (that apparently had a Triumph TR2 engine). But clearly cars were a life-long love for the designer. He returned to the subject many times in album covers for Donald Byrd, Hank Mobley, and Stanley Turrentine, often recreating similar vantage points and compositions among them. While there are people present in the images, the cars are the real stars, with humans occupying a lesser position in the background. The headlights become just that, a head, of a very foreshortened body of an automobile while human bodies are compositionally truncated or subsumed by the cars. In an age where we are facing the very real possibility of sharing the road with driverless cars, this aesthetic strategy seems to take on increased relevance, but Miles was creating these photographs before we even had Knight Rider or even Herbie the Love Bug.

Reid Miles' photography and design for Stanley Turrentine's Joyride, 1965

So if Miles' personal passion really is laid bare in the album covers above, it only makes sense to finish by looking at which cars he loved enough to include in his work. With the help of my friend Alex, we present below our best guess on the make and model of these vehicles.

1964 Jaguar Series 1 XKE Convertible

1965 Cadillac Coupe Deville Convertible

1962 Cadillac Eldorado Convertible

Like the cars he loved, Reid Miles' work is legendary and there are a lot of great stories out there regarding his life's work. Below are some resources I used that talk about different aspects of Miles' career.

Designer Viljami Salminen wrote a great blog entry on Reid Miles' days at Blue Note.

Gerald Watson's interview with Wayne Adams can be found on the former's blog New Ish.

That awesome image of three Warhol/Miles album covers came from the fantastic blog LondonJazzCollector, check it out!

The People Magazine interview can be found on their archive here.